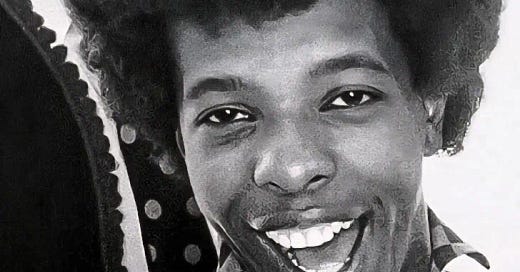

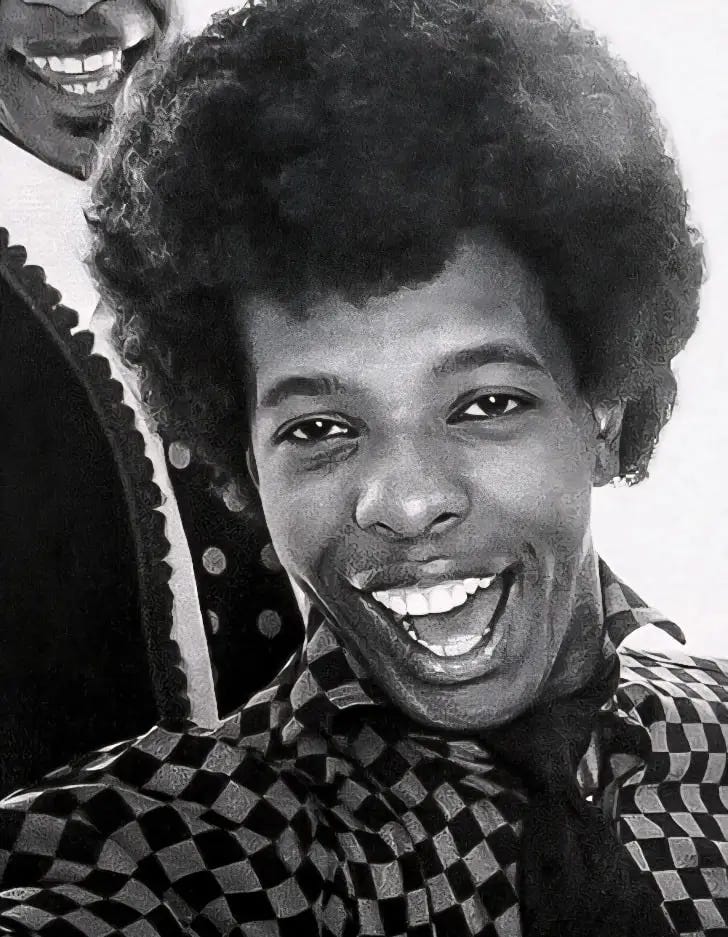

(Scroll to the end to watch Syl and the Family Stone perform “Thank You.”)

He stood onstage like a prophet who refused the sanctity of robes. Sequins instead. Boots like battle flags. A grin that knew too much. Sly Stone didn’t just blur boundaries. He crushed them underfoot and replaced them with funk, feedback, and ecstatic refusal. In his music, white and Black didn’t so much hold hands as grab each other by the collar and get down. In his band, women weren’t backup; they were co-conspirators. And in his vision, the revolution would not be televised, but it might be broadcast from a haze of purple light, sweat, and righteous distortion.

Sly, born Sylvester Stewart, died this week at the age of 82.

He arrived just as the 1960s began to hemorrhage idealism. The Black Panthers had the guns, but Sly had the grooves. If the Panthers were the shield, Sly was the spell. Everyday People was an anthem in disguise; a sugar-coated grenade lobbed at a segregated radio dial. His multiracial, multi-gendered band was not just a novelty; it was an insurgency. At a time when America preferred its music like it preferred its neighborhoods, neatly zoned and racially quarantined, Sly mixed gospel, soul, acid rock, and whatever cosmic residue fell from the sky that day. He gave white kids something to dance to and Black kids something to dream through. He built sonic bridges across America's psychic apartheid.

And yet, Sly wasn’t swallowed up by the myth of uplift. He saw the rot in the floorboards. His later songs, paranoid and scattered, were not the symptoms of a fall from grace; they were documents of betrayal. There’s a Riot Goin’ On wasn’t a soundtrack to a party; it was the sound of the party being busted up, the lights flicked on, the bodies scattered, the floor sticky with disillusionment. He named it before the news did.

What can today’s progressives learn from Sly? First, that unity isn’t built through slogans or saviorism; it’s built in the groove, in rhythm, in lived and broken contradiction. He didn't pander to purity. His vision was messy, ecstatic, queer, polyphonic. Today’s movements could use less choreography and more jam sessions: spaces where dissonance isn’t a threat, but the beginning of a new harmony. Sly's politics were not on a placard. They were in the bassline. They didn't ask permission.

Second, Sly reminds us that joy is insurgent. That a drumbeat can be a manifesto. That dancing isn’t escape: it’s resistance. He teaches us to demand pleasure in our politics, not as an afterthought but as a strategy. That the revolution should not only be righteous; it should be funky.

And third, that even prophets falter. Sly disappeared for decades, haunted by the same demons America breeds and refuses to name.

But the echo remains. In the music. In the movements. In the stubborn insistence that we are, still, everyday people: angry, ecstatic, fractured, and free.

Beautiful tribute to an American original. I first saw Sly before he became a big star. He was at the initial stages of offering his musical awakening to the world. It was a club in East Lansing, Michigan called The Brewery. When Sly entered and strolled across the club to mount the stage and begin his performance, the room was electrified. The man had more charisma in his pinky than most contemporary performers can muster with teams of PR men and handlers. He is deservedly a legend. His music speaks for itself.

Michael Morrill: a gift for putting thoughts into words. A pleasure to read your eloquent tribute to Sly and putting his life and work into the context of what's happening in the here and now. We should all have such courage as to put ourselves so fully out there to speak our truth.